Callum Young and Andy Bell

Mental health needs assessments (MHNA) are a fundamental foundation for commissioning and delivering services which truly meet the needs of local communities. Only by understanding the breadth and diversity of local needs can services work to meet them. And at a time of rising mental distress, commissioning the most effective support is more essential than ever. Building on our report with Public Health England about best practice for MHNAs, and drawing on examples from around the country, this resource sets out the key factors for producing an impactful needs assessment.

What is a mental health needs assessment?

A mental health needs assessment (MHNA) is a process by which a local council or other public body seeks to understand the mental health and wellbeing of its population, and how well people’s needs are being met by the services that are available. It is often one aspect of a local joint strategic needs assessment (JSNA) which is a statutory role of local authorities with public health responsibilities. It is a fundamental foundation for the provision of mental health services that meet the needs of people and communities.

Introduction

In 2016, Centre for Mental Health published a report in conjunction with Public Health England which outlined best practice for a joint strategic needs assessment for mental health. The aim was to help produce mental health needs assessments that are comprehensive and impactful. Since its publication, this report has been integrated into the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities’ MHNA toolkit.

While many of its central recommendations remain relevant today, there have been major changes to our health landscape since the report was published. In this new resource, we update our MHNA guidance to help tackle the issues which have since arisen and reflect best practice as we understand it now.

To do this, we met with representatives from four local authorities where MHNAs have recently been produced:

- Bradford

- Bristol

- Wandsworth and Richmond

- Warwickshire.

We discussed their experience of producing an MHNA and the challenges they faced while doing so. Additionally, we assessed the impact of these MHNAs, and identified key features which determined their successes and limitations. In this resource, we outline critical factors for producing a high-impact MHNA.

As well as these conversations, we reviewed the following successful MHNAs to identify their key features:

- Bristol (2024)

- Cambridge and Peterborough (2024)

- Wandsworth (2023)

- Warwickshire (2023)

- Kingston (2022)

- Oxfordshire (2021)

- Shropshire (2018)

- Solihull (2019)

- Coventry and Warwickshire (2021)

- Bradford (2020)

- Luton (2018)

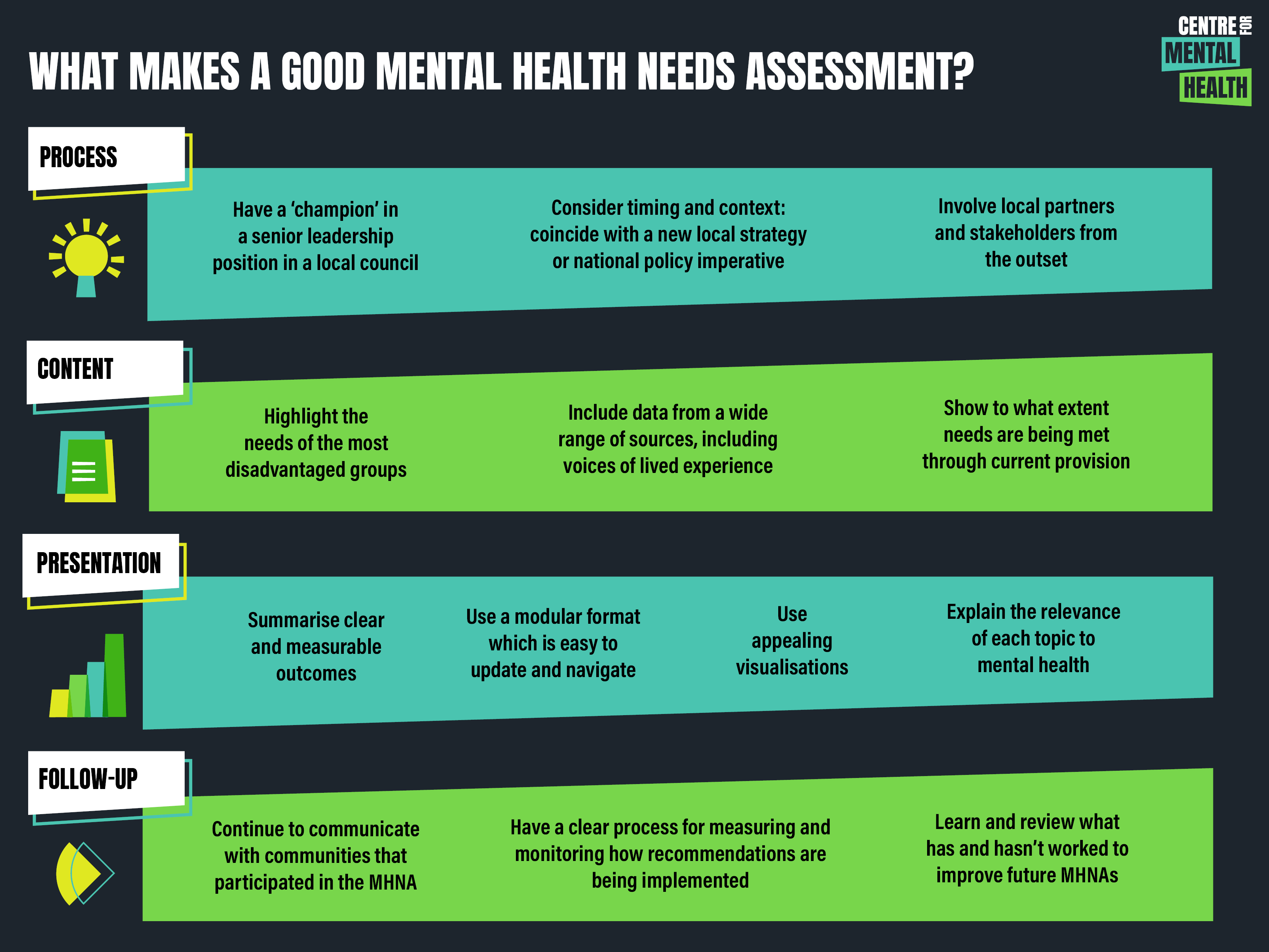

Key features of impactful MHNAs

Process

- Leadership: Having a ‘champion’ in a senior leadership position in a local council creates demand for the work and boosts its chances of success

- Stakeholder engagement: Involving local partners and stakeholders from the outset maximises both the breadth of inputs and the likelihood of lasting impact

- Timing and context: A mental health needs assessment that coincides with a new local strategy or national policy imperative is more likely to get used.

Content

- Including data from a wide range of sources: Data from voluntary and community sector organisations, social care, and preventative services, including voices of people with lived experience, is essential to paint a full picture, not just statistics

- Marginalised communities: Highlighting the needs of the most disadvantaged groups makes inequalities visible, and can identify emerging trends or concerns that require attention

- Service provision: Data must not only show where need exists, but to what extent this need is being met; information should be collected around effectiveness and what gaps exist in current provision.

Presentation

- Appealing visualisations: Graphs should be easy to understand, including when used without the context of the overall report. Consistent colour schemes, well labelled axes, and graph titles are essential for this

- Modularity: Reports should be modular and easy to update, and allow the reader to navigate between relevant sections of the MHNA

- Clear recommendations: Successful MHNAs have clear and measurable outcomes. These should be summarised at the start or end of relevant MHNA sections

- No assumed knowledge: MHNA authors should explain the relevance of each topic to mental health, include an acronym dictionary, and transfer recommendations from other joint strategic needs assessments that are relevant to mental health

- Covid and the cost-of-living crisis: MHNAs should explore how recent crises and trends are affecting people’s mental health sensitively.

Follow-up

- Monitoring outcomes: Having a clear process for measuring and monitoring how recommendations are being implemented, and with what effect

- Communication: Continuing to communicate with communities that have participated in the MHNA and can help to implement recommendations and hold systems and services to account for acting on them

- Evaluation: Learning and reviewing what has worked and what hasn’t in order to improve future MHNAs and their implementation.

Process success factors

Ensure that mental health needs assessments are championed by someone with a senior leadership position

Ensure that mental health needs assessments are championed by someone with a senior leadership position

This ensures that MHNAs receive adequate resources, and that their recommendations are taken seriously by the local authority. To support this, it may be advantageous to produce an MHNA when there is demand for such work. For example, capitalising on a new mental health strategy will ensure that there is an appetite for the evidence-based recommendations that an MHNA can produce. Furthermore, changes in national policy may provide perfect context for an MHNA. Often, national policy can provide the funding for implementing an MHNA recommendation. Making these recommendations when the news of such funding is fresh increases the likelihood of their being taken up. This, combined with allyship within senior leadership, will ensure the impact of the MHNA is maximised.

Not all recommendations in an MHNA can be executed by public health – they need the support and active participation of the council as a whole. By working across the council, an MHNA allows all council workers to recognise their contribution towards reducing risk factors and boosting protective factors for mental health. In Wandsworth, for example, taking this approach allowed the council to produce and advocate for a cross-council strategy.

Engage relevant stakeholders throughout the process

Engage relevant stakeholders throughout the process

MHNA authors report that the process, more so than the resulting document, is critical to producing sustainable impacts. By bringing together stakeholders, and building lasting networks between them, there remains an action team who can come together and implement changes according to the MHNA’s recommendations. Included in these stakeholders may be commissioners, service providers, service users, and decision makers. Building allyship between these people will have lasting impacts on an area’s mental health landscape.

Stakeholders are a valuable resource when conducting an MHNA. Not only do they have information which may not be publicly available, they also manage networks of service providers and service users which can offer a valuable qualitative perspective. This will supplement information in the MHNA, in cases where data is lacking. It also helps to build relationships with the people who will be responsible for promoting and implementing the recommendations in an MHNA. Wandsworth’s MHNA used stakeholder focus groups to supplement the data within the report. This approach ensures that key stakeholders are involved in the MHNA process, and that critical relationships are formed. By fostering this allyship, an action network can be formed which later helps to implement MHNA recommendations.

For Bradford’s MHNA, authors were able to use the Bradford Mental Health Provider Forum to get in contact with and collect survey responses from service users. They also emphasise their intention to repeat and update the survey, allowing this to serve as a ‘living’ resource.

Timing and context are important for maximum impact

Timing and context are important for maximum impact

In Warwickshire, there have been two recent MHNAs. One was aimed at adults, and another at children and young people. Work on the latter was timed to coincide with the re-commissioning of local CAMHS services. This meant that any service-related recommendations could be incorporated into the commissioning process.

In Warwickshire, there is also a JSNA prioritisation process, which dictates where a JSNA will be of most use. This means that the health and wellbeing board are involved in the production of a JSNA, even prior to its start. As such, the JSNA is shaped by local decision makers, and its recommendations form part of their priorities.

In 2020, Bradford produced an MHNA in response to the pandemic. The team identified that Covid would have predictable and unpredictable consequences, and wanted to act before these materialised to their fullest extent. The MHNA was perfectly timed according to local and national context.

Additionally, the team recognised a vibrant community and voluntary sector, which was rapidly adapting to the constraints of Covid restrictions. By making this observation, they were able to position themselves to learn from these innovations and develop their own practice.

In Bristol, a JSNA working group meets three times a year. This group includes council officers, elected members and external partners. It looks at the most recent updates to the data profiles (explored below), and calls focus to particular issues in the city. This is fed back into the JSNA process, therefore creating a circular system that ensures focus is constantly prioritised on the most pressing issues.

Content success factors

Formal data can be supplemented by alternative sources of knowledge

Formal data can be supplemented by alternative sources of knowledge

The national Fingertips database provides local councils with a valuable source of data to support an MHNA, but it is not a replacement for local sources of knowledge and understanding. Granular data can be accessed from a wide range of local sources (not just statutory services). Local charities and community groups will have data from which accurate local estimates can be drawn. Additionally, where local data is missing altogether, NICE guidelines provide evidence-based recommendations at a national level, which can be adjusted according to the demographic makeup of a local area.

Warwickshire highlights that small amounts of important data are more impactful than a wealth of information which is hard to interpret. The job of an MHNA is to highlight the most pressing concerns and propose solutions to them.

In Bradford, the voluntary and community sector provided much of the data for the MHNA. This includes data from their own services, and qualitative feedback from their service users. Part of this qualitative information was garnered from questionnaires, which were disseminated by these partners. This, in the mind of the interviewees, helped to make the MHNA feel coproduced and compensate for a lack of statutory data at the height of the pandemic. The help of the voluntary and community sector from the outset of the process was, according to the Bradford team, the key to the success of their project.

In Wandsworth and Richmond, a lot of the available data was outdated and available only at a national level, limiting its utility. Modelling helped to rectify this and make predictions about areas of highest need.

This was also supplemented by asking service users and service providers to give their perspectives. Services were essential to providing recent data which was not otherwise available. Additionally, focus groups and ward visits meant that their qualitative experiences could be included, and take the place of missing data. These personal perspectives helped to humanise the report’s narrative, and this was a compelling force in the education of elected members.

Provide data on current services and gaps

Provide data on current services and gaps

It is important to show a complete picture of the care being provided within a community, including social care and wider forms of support as well as NHS mental health services. For example, presenting referrals for mental health services alone is insufficient; these should be presented alongside the rate of referral acceptance. In cases where the gap between referrals made and referrals accepted increases, the extent of provision is worsening. This is presented well in Wandsworth’s MHNA.

Where available, outcomes data should also be included. In Shropshire’s MHNA, local outcomes data is compared to the national average, allowing commissioners to see how effective their services are in relation to others.

There is also benefit to showing the existing provision for preventative programmes. In Kingston’s MHNA, there is specific reference to spending on children’s and women’s services, which are integral to supporting people at greater risk of adverse health impacts. This shows where money is currently invested, and highlights any potential shortfalls which can be addressed in the ways funding is distributed.

Highlight the needs and experiences of marginalised communities

Highlight the needs and experiences of marginalised communities

People from racialised and marginalised communities are more likely to have poorer health outcomes due to structural racism and inequities. They are also more likely be exposed to risk factors for poor mental health, such as poverty, poor housing and limited opportunities. To be fit for purpose, an MHNA should report on the extent to which the needs of people from racialised and marginalised communities are being met. This has, for the most part, been included in the MHNAs in our case studies where service use is divided according to ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

Coventry and Warwickshire’s MHNA refers to groups that are not commonly considered in terms of facing adverse impacts to their mental health, such as frontline workers (for example, care workers, doctors and nurses). The impact of Covid, and the subsequent cost-of-living crisis, has been disproportionately high for many people in these occupations. An MHNA must holistically tackle these issues and be able to identify emerging groups of people experiencing significant or growing risks to their mental health. Bradford’s MHNA presents this in table format, highlighting issues for specific communities, and proposing potential solutions.

Bradford’s MHNA also carefully considers the impact of financial insecurity on mental health. This was looked at in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, but the data are doubly pertinent in midst of the cost-of-living crisis. With poverty levels at record highs, the rising cost of essentials is causing substantial harm to people’s mental health. Interventions to tackle financial strains, such as support with problem debt, work, and benefit entitlements, can have significant health benefits.

Presentation success factors

Mental health needs assessments must be presented well and easy to read

Mental health needs assessments must be presented well and easy to read

It is essential that data included in an MHNA is accessible and easy to understand; summaries of information can also be very helpful. Authors disagree about the right length of an MHNA. Some people insist that being concise is of paramount importance. Others believe that arbitrarily limiting length can restrict the quality of information included in an MHNA. Ultimately, both long and short MHNAs can be successfully impactful. What matters most is that the information is presented clearly to the audience.

For most purposes, the central messages will be conveyed through the report’s figures. Most of the MHNA’s intended audience will not read the text in detail. Instead, they will seek to glean a general message from graphs and data tables. Additionally, these visualisations can be utilised by people advocating for the report’s recommendations. As such, it is essential that these are self-explanatory and sufficient to convey the report’s key conclusions.

The MHNAs in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, Bradford, Bristol, and Coventry and Warwickshire used visually appealing graphics to convey key messages. Consistent design features help to make graphs easy to interpret at a glance; for example, using consistent colours to represent localities, and using clear titles and axis labels.

Some types of visualisations are particularly highly regarded. For example, a heatmap of different determinants can help to illustrate areas with greatest need for intervention. More localised spatial data will enhance the understanding of the geographical distribution of need, with Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs) forming the gold standard. Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, Shropshire, and Kingston provide good examples of localised data being used in an MHNA.

For instance, Kingston’s MHNA uses colour-coded data tables to facilitate comparisons between Kingston, London, and the national average. They show where Kingston performs better (green) or worse (red) than the country as a whole on specific health indicators. This consistent and universally-recognised colouring system makes the data easy to interpret at a glance.

There is value in plotting longitudinal data, both between and within years. This can help to identify whether there are surges in demand during certain months, and therefore highlight additional risk factors, for example, a rise in service use during winter (as seen in Kingston’s MHNA).

Some JSNAs and MHNAs, despite containing excellent content, are densely packed with text. A lack of headings or visualisations can make it difficult for people to absorb the document and deter them from engaging thoroughly with its recommendations. This is especially true for decision makers who may have less specialist knowledge of mental health.

In contrast, Kingston’s MHNA uses short paragraphs and includes lots of white space. This makes the report easy to read, and generates a sense of momentum in the reader, which makes it easier for them to internalise the key findings. This is also true of Coventry and Warwickshire’s MHNA, which has relatively little text on each page, making its findings easy to digest and retain.

Modular and interactive outputs can make an MHNA easier to use and update

Modular and interactive outputs can make an MHNA easier to use and update

It is becoming increasingly common for local authorities to modularise their MHNAs, producing them in bite-sized pieces, often with interactive tools for readers to use. Although ways of doing this vary between councils, the core logic remains the same: by dividing a larger MHNA report into several chapters, and independently uploading and updating these chapters, the authors produce a flexible and relevant resource. This means that decision makers can access the most up-to-date information whenever they need to refer to an MHNA. It also ensures that MHNAs have longevity and can be used beyond the point of initial publication.

In Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, the MHNA is split into digestible chapters. Each chapter discusses a different topic – for example, chapter 1 explores environmental determinants of mental health, while chapter 2 explores population determinants. Each of these chapters is uploaded independently of each other and made available as and when completed. Within these chapters, different sections are hyperlinked, facilitating navigation between the modules.

A similar, yet more novel, approach has been adopted by Bristol. Instead of relying solely on a traditional JSNA format, the council’s public health team produces data profiles which are updated annually. These are short documents, stored and accessible online in a central repository, which include relevant data and some additional context. To supplement these profiles, there are also detailed JSNA reports which make specific recommendations based on the latest data from the repository.

There is also an online dashboard for Bristol’s Quality of Life survey, where users can compare localities. This highly interactive system allows users to filter the data according to their interest, making it an incredibly useful tool for different teams to prioritise their own areas of concern.

In our conversations with Warwickshire, there was a big emphasis on their online dashboard. This new system for delivering JSNAs came in response to feedback that a traditional JSNA is long and boring. The new system, instead, is iterative. It is updated as new data becomes available, and does not require the prolonged process of producing an entirely new report. This ensures that the JSNA has up-to-date data and recommendations.

While Wandsworth and Richmond’s current MHNA adopts a more traditional format, they intend to update data in the report as it becomes available. In this sense, the report is a living resource, akin to Warwickshire’s and Bristol’s. Though less interactive, this represents a way of futureproofing the work and maintaining its relevance.

Make recommendations clearly and consistently

Make recommendations clearly and consistently

Recommendations should be clear, explicit, and contain a mechanism for evaluation. In Bradford’s MHNA, the recommendations are split up according to different categories (for example, communities, financial issues, leadership and accountability). This makes them easy to absorb and means that stakeholders can be directed to the information most relevant to them.

Effective MHNAs vary in where they place their recommendations, but they are consistently clear and are often repeated. Wandsworth provides a prime example of this, making its recommendations at the start of the MHNA and repeating them throughout the report so that the subsequent evidence can be read with them in mind. Wandsworth has also produced a separate slide deck which includes the recommendations, providing a tool for council officers to present the key findings. Shropshire’s ‘Key Messages’ slide deck serves a similar function.

At the end of each section, Wandsworth’s MHNA includes a box highlighting the key findings. Luton’s MHNA does this at the start of each section, allowing the reader to absorb key messages and recommendations without having to digest the whole report. The executive summary is written in table format, with ‘key findings’ and ‘recommendations’ as separate columns. This makes it very easy to link recommendations to their supporting evidence, and summarises the subsequent report succinctly. In contrast, Shropshire’s MHNA contains a summary at the start of each chapter.

Don’t assume readers’ knowledge about mental health

Don’t assume readers’ knowledge about mental health

Limiting a report’s accessibility means reducing its influence. Accessibility enables a broader audience to engage with the findings, resulting in a wider coalition of organisations who can support the MHNA’s recommendations.

The reader might happen to be an expert in public health, but may not have a deep understanding of mental health. MHNA authors should remind the reader why the themes explored in the document are relevant to the question of mental health. This was surprisingly rare in the examples reviewed for this publication.

Although many readers will have a keen interest in public health or mental health, their wide portfolios might mean that they are unfamiliar with specific acronyms used in the report. An acronym dictionary can help to increase accessibility, and therefore expand the report’s audience, as expertly demonstrated by Wandsworth’s recent MHNA.

Kingston’s MHNA does not assume readers’ prior knowledge, and includes relevant recommendations from JSNAs on different topics that may also benefit people’s mental health. This not only makes the document accessible to non-expert audiences but also helps to reinforce the importance of actions that will benefit both mental and physical health.

Address Covid and the cost-of-living crisis with sensitivity

Address Covid and the cost-of-living crisis with sensitivity

National crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis undeniably have a huge impact on people’s mental health. Addressing these concerns requires awareness and sensitivity. Warwickshire’s director of public health produced an annual report on health and the high cost of living. Our interviewees highlighted the need to address the impact of high costs, without being drawn into the political arena. They identified the cost of living as a risk factor which can increase stress and therefore mental ill health. They highlight the fact that MHNAs are tools for the health and wellbeing board, which contains both elected members and council officers, and which therefore has to engage with highly politicised issues but be informed by politically impartial and epidemiologically reliable evidence.

The impacts of these major crises, and others to come, create especial challenges for public health workers, whose role it is to protect the public from harm, when such harm is happening on a large scale. Needs assessments including MHNAs have value in being able to identify not just the immediate risks but also the longer term ‘shockwaves’, such as the traumas generated by the Covid-19 pandemic and this summer’s racist violence in many communities. MHNAs allow for an honest discussion of the impacts of these events on people’s mental health in such a way that supports action to address the harms that have occurred.

Follow-up success factors

Mental health needs assessments outcomes must be monitored

Mental health needs assessments outcomes must be monitored

Monitoring outcomes ensures that local authorities and their partner agencies are held to account. This process can also bring to light new information to update the MHNA with. As such, it is imperative that they are designed in a way that facilitates this. In this way, if the evaluation of the MHNA outcomes reveals that a particular recommendation has proved unsuccessful in improving mental health, the MHNA can be adjusted to reflect these findings.

Continued communication with communities is essential

Continued communication with communities is essential

In Warwickshire, the mental health collaborative (comprised of community and NHS providers) worked together to share the insights and priorities of the MHNA. This involved the active dissemination of recommendations and findings. This resulted in a new local workplan, based on ten key priorities derived from the MHNA. This is something which has been replicated across the public health team, with Warwickshire’s recent suicide prevention strategy referring a great amount to a relevant JSNA. The same is true for a programme of work focused on preventing self-harm among children.

Warwickshire’s experience highlights that the conversations had during the MHNA process are almost as important as the MHNA itself. These conversations ensured that the document was tailored to the needs of the reader, and built relationships which helped to disseminate the MHNA’s key findings. By forming these alliances, there is an audience ready to take the MHNA recommendations on board, and advocate for them within their own job role.

In Bradford, relationship building was an integral part of the MHNA process. The report was presented to the health and wellbeing board alongside an NHS colleague, providing the recommendations with additional weight. By working with the community sector, the team was also able to secure additional provision from these organisations, which helped to provide long-term mental health infrastructure in Bradford.

Sharing stories from the community sector in Bradford was extremely effective in compelling decision makers to act on the MHNA’s recommendations. This demonstrates the importance of prioritising these relationships throughout the MHNA process in order to ensure it has a positive impact. The team also highlighted the need to maintain these community group relationships, and that this should be a priority in relation to funding decisions.

In Wandsworth and Richmond, a partnership approach was central to the MHNA. They set up a steering group, which included health professionals, service users, residents, community organisations, and the local mental health trust. These stakeholders identified the recommendations that they wanted to focus on, increasing buy-in and ensuring a wide range of voices and perspectives were included in the work. The result was a straightforward approach for implementing key programmes, which were warmly welcomed by the relevant stakeholders.

In Bristol, a monthly bulletin goes out to stakeholders across the area. This includes information about which data profiles have been updated, and recent publications of full JSNA reports. By including stakeholders in this process, everyone is kept up to date with the most recent information. This helps services to formulate their own internal recommendations, and passes some power to the stakeholders. In addition, the data can be used by community groups to apply for grants, which provide the funding for more effective services. This creates a dynamic service landscape where the most relevant data is available to shape provision.

Evaluate impact and learning

Evaluate impact and learning

Although most people we interviewed acknowledged the importance of impact assessments, many report that this was not done for their MHNAs. In Warwickshire, there was little formal evaluation of the MHNA’s success. Despite this, the team themselves have been keeping an anecdotal record of its impact, and the new online dashboard allows them to track clicks and downloads. They plan to build an assessment process into the future JSNA programme.

There is also value in getting an outside perspective on the success of an MHNA. In Warwickshire, a children and young people’s partnership (sitting under the health and wellbeing board) monitors the recommendations made in the children’s MHNA, and an independent organisation was engaged to track the overall progress of the area’s mental health agenda. Although this isn’t a specific evaluation of the MHNA, it provides valuable intelligence about its impact.

In Bradford, although there was no formal evaluation, many of the MHNA’s recommendations were adopted, outliving the context of the pandemic they were written in. Some new services are being commissioned with these recommendations in mind, including a service for racialised communities. This highlights how informal monitoring can help to promote the MHNA’s ideas. However, a formal evaluation and longevity strategy would help to consolidate these impacts in the long term.

Conclusion

The goal of an MHNA is to influence the policy agenda of local government and its partners. Therefore, it must be comprehensive, compelling and engaging. In understanding the mental health of a place, it is uniquely able to describe the risk and protective factors for mental health and wellbeing, to assess levels and patterns of mental distress and mental illness, and to gauge how well people’s needs are currently being met by public services in that locality.

The process of conducting an MHNA is as important as the content and presentation of the document itself. An inclusive, curious and open process can generate deeper understandings about how people’s mental health exists in the context of their lives, and build new cross-sector relationships which can support advocacy for and implementation of mentally healthier policies.

A good and effective MHNA is at the heart of building mentally healthier places, and thus a mentally healthier nation. The state of the art of a good MHNA is always evolving: it has changed since we originally explored their success factors, and it will continue to do so in the years to come. But its essential purpose remains steady and its importance to addressing mental health inequalities is undiminished.

Centre for Mental Health has worked with local authorities, integrated care systems, combined authorities and service providers across the country to help them understand local needs. Find out how we could support you to produce an effective mental health needs assessment.

Ensure that mental health needs assessments are championed by someone with a senior leadership position

Ensure that mental health needs assessments are championed by someone with a senior leadership position